On the evening of their arrival in Berlin, Söderhjelm brought Sibelius

to the Kroll Oper, where they saw Don Giovanni with the great

Portuguese baritone Francisco d’Andrade (1859-1921) in the title

role, who was making his debut in the German capital that same year1:

this first contact with one of Mozart’s operas opened unsuspected

horizons for Jean. He hurried to to inform Christian, who the 18

September replied asking him if the opera was as really beautiful as

imagined. His letter of the 2 October to Uncle Pehr showed him

already confronted with difficulties of an artist from a country

considered strange in a great cosmopolitan metropolis: ‘I have

almost become a real Berliner, though without drinking beer. The

doctors have forbidden it. There is very much to see and hear, and

it will be even better when the season starts. My composition

teacher Professor Albert Becker, earns 100 roubles a day and has the

air of a composer of days gone by. I have not really understood

his method. I am deep in the study of fugues, and will soon start the

violin. Last summer I was a great success as soloist both at Lovisa

and at Lahis. Here in Germany they really know how to put you

down. The only reply is to do the same to them. Believe me it is

difficult to be the advocate of a country as little known as Finland.

There are many Finns here. People here greatly admire composers.’

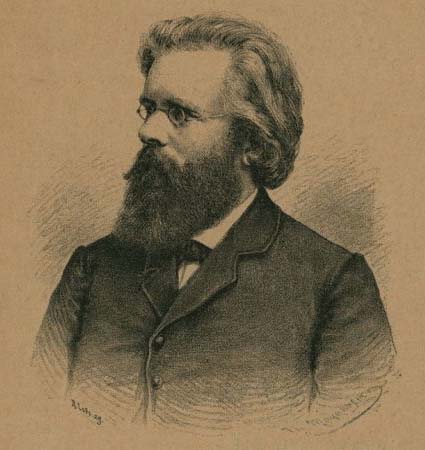

Albert Becker

Albert Becker

Having

lost his ‘favorite student’ Wegelius felt empty, it was as if

Sibelius had taken ‘half of the Institute’ with him in his bags. Hardly arrived in Berlin, Jean had to

spend a few days in hospital. The 29 September, he sent the first

report of his activities to Wegelius: ‘Becker is a real wig from

head to foot. In looking at my quartet, he almost had

an attack (he is totally lost by the way I use alternating major and

minor forms in the same triad). He just glanced over my music, sung

the second theme of the finale (he is incapable of playing it) and

pretends, not be able to grasp it, that I wrote it by calculation.

He was above all shocked by [a wrong relation, but] should listen to

how this phrase sounds an octave lower. He has started to teach

me to a maximum in strict style, no doubt he has nothing to say, but

it is very fastidious. Becker is very rigid in his attitude

towards me, but with time he will surely soften up.’ These

criticisms as regards a teacher that he himself had chosen annoyed

Wegelius: ‘Mon Cher Jean [in French]! The composer of the mass in B

flat minor [opus 16, 1878] and the [oratorio] Die Wallfahrt nach

Keevaler (The Pilgrimage to Keevaler) is not “a wig from head to

foot”. Get this idea out of your head!’ (4 October). In spite of

receiving the second prize from the Society of the Friends of Music

in Vienna for his symphony n°2 in G minor, Becker was above all

known for his religious works. The German Emperor Wilhelm II, an

enemy of modern music, very much appreciated him and to keep him in

his entourage, he prevented him from accepting the position as

cantor at Saint Thomas of Leipzig. In 1891, he appointed him

Director of the Königlicher Domchor (Royal Cathedral Choir) in

Berlin: a position once held by Mendelssohn, which Becker was to

hold until the end of his life eight years later. His motto, which

he never ceased to repeat to his students, was: Lieber langweilig

aber in Stil (Be bored if you wish, but in style).

Becker,

who enjoyed the merited reputation of a professor of counterpoint,

and with who Sibelius studied in private, considered that with

Wegelius, his new student had wasted his time, a judgement that

Jean, his self-esteem hurt, and who had in reality benefited from a

solid training in Helsinki, kept prudently to himself. The 6

November he wrote to Wegelius: ‘Becker does not want to speak of

anything but his fugues. To be limited to such things is really

boring. I now know the German Psalter from beginning to end and vice

versa. You asked me what I am working on and would like to see my

finished exercises. In my opinion not of much interest. As

everything is forbidden, what can I write? I have analysed several

Bach fugues (and even some of Becker’s in person) as well as some

Bach motets. I am now going to write instrumental fugues. I

have learnt to never argue with Becker, not to show my feelings

[and] never plead the cause of my idiocies.’ From this period a

piece for four real voices, written by Sibelius has survived, with Beckers corrections of the words Mein Gott, Mein Heiland, ich

schrie Tag und Nacht vor dir (My God, my Saviour, I cry night and

day before You).

Becker,

who enjoyed the merited reputation of a professor of counterpoint,

and with who Sibelius studied in private, considered that with

Wegelius, his new student had wasted his time, a judgement that

Jean, his self-esteem hurt, and who had in reality benefited from a

solid training in Helsinki, kept prudently to himself. The 6

November he wrote to Wegelius: ‘Becker does not want to speak of

anything but his fugues. To be limited to such things is really

boring. I now know the German Psalter from beginning to end and vice

versa. You asked me what I am working on and would like to see my

finished exercises. In my opinion not of much interest. As

everything is forbidden, what can I write? I have analysed several

Bach fugues (and even some of Becker’s in person) as well as some

Bach motets. I am now going to write instrumental fugues. I

have learnt to never argue with Becker, not to show my feelings

[and] never plead the cause of my idiocies.’ From this period a

piece for four real voices, written by Sibelius has survived, with Beckers corrections of the words Mein Gott, Mein Heiland, ich

schrie Tag und Nacht vor dir (My God, my Saviour, I cry night and

day before You).

Ferruchio Tammaro noted that at this rhythm Sibelius

would have become another Max Reger. In spite of his doubts Becker’s

lessons were finally very useful and the fact that in Berlin, he was

simply a student amongst others, and not the future hope of the young

Finnish music. His incertitude was witnessed by these words noted

by by him the 14 October 1889 on the back of a receipt from his

teacher: ‘Try to be a man and always remember your own

responsibilities. Do not give in to feelings, but harmoniously

develop your gifts. Do not imagine being anything other than what

you are. Do not dream of becoming a celebrity. Work intelligently.

Si mal nunc et [!] olim sic erit.’ Becker finally thanked

Wegelius for having sent him den lieben jungen Mann (the charming

young man), adding: Er interessant mich sehr und ist entscheiden

begabt (He interests me very much and is decidedly very gifted).

Berlin, a

musical metropolis

Musical

life in Berlin offered captivating compensations. There were no

leading composers resident in the city, but the number of artistic

events were many and of a high quality, notably philharmonic

concerts directed by Hans von Bülow (1930-1894). It was in this

context on the 31 January 1890, shortly after its creation in Weimar

(11 November 1889), Sibelius attended a performance of Don Juan,

the work with which Richard Strauss made his shattering entry into

‘modernity’. After the performance, he told Ekman, ‘a timid young

man with a head of long hair mounted the stage to in response to the

applause. His reaction can only be imagined to this composer only

eighteen months older than him, but already in full glory and

capable of leading the orchestra with such virtuosity and stupefying

mastery. In the same programme was the overture of Deux Journées

by Cherubini, the symphony in E flat major N°99 of Haydn, the finale

of which was given an encore, and the prelude to Wagner’s

Lohengren. A few days later, during a popular

concert of the Philharmonic, Strauss himself directed Don Juan

with greater flexibility in the tempos and with more clarity in his

sonorities than Bülow: at least this was the opinion of the editor

of the Allgemeine Musik-Zeitung, Otto Lessman (1844-1918),

later a great defender Sibelius in the German capital. ‘Bülow really

understands nothing of poetic music, he has lost the hang of it! Thank God, yesterday evening gave me the satisfaction of presenting

my work as it should be to the Berlin public. […] I conducted the

symphony a good third faster’ (Strauss to his parents, 5 February).

In

October 1889, Sibelius attended a performance of Dvorak’s symphony

in D minor in the presence of the composer himself, Brahm’s violin

concerto, as well as two overtures: La Belle Mélusine by

Mendelssohn and Beethoven’s Leonore III. Previously he had

for the first time seen Wagner’s Tannhäuser and The Master

Singers, and wrote of it to Wegelius the 29 September, taking

care not to hurt the feelings of this enthusiastic partisan of the

Bayreuth musician: ‘It is indisputably very powerful. When we see

each other again I will tell you about my reactions in more detail,

and will tell you what I felt. This music was a mixture surprise

deception and pleasure, etc. for me. I was ill both evenings, but be

assured I will never forget them.’ In a new letter to Wegelius (6

November), he declared that the overture of Fées was nothing

other than an imitation of Weber, but to Aunt Evelina, he wrote that

he had been ‘astounded’ by Wagner. At the same concert as the

overture of the Fées, he had been able to listen to a psalm of

Liszt’s and two ‘marvellous pieces’ by Berloiz (two extracts from

Lelio). In the correspondence of Sibelius there is no mention of

Verdi’s Othello, the Berlin premier had taken place 1

February 1890, or Wagner’s Ring, which was performed in its

entirety in the autumn of 1889.

In

October 1889, Sibelius attended a performance of Dvorak’s symphony

in D minor in the presence of the composer himself, Brahm’s violin

concerto, as well as two overtures: La Belle Mélusine by

Mendelssohn and Beethoven’s Leonore III. Previously he had

for the first time seen Wagner’s Tannhäuser and The Master

Singers, and wrote of it to Wegelius the 29 September, taking

care not to hurt the feelings of this enthusiastic partisan of the

Bayreuth musician: ‘It is indisputably very powerful. When we see

each other again I will tell you about my reactions in more detail,

and will tell you what I felt. This music was a mixture surprise

deception and pleasure, etc. for me. I was ill both evenings, but be

assured I will never forget them.’ In a new letter to Wegelius (6

November), he declared that the overture of Fées was nothing

other than an imitation of Weber, but to Aunt Evelina, he wrote that

he had been ‘astounded’ by Wagner. At the same concert as the

overture of the Fées, he had been able to listen to a psalm of

Liszt’s and two ‘marvellous pieces’ by Berloiz (two extracts from

Lelio). In the correspondence of Sibelius there is no mention of

Verdi’s Othello, the Berlin premier had taken place 1

February 1890, or Wagner’s Ring, which was performed in its

entirety in the autumn of 1889.

His

principal revelation in Berlin was Beethoven. Bülow opened the

autumn season with Eroica (14 October 1889), and ended it

with The Ruins of Athens and the Ninth (16 December),

and then inaugurated the spring season with the Fifth (13

January 1890). Sibelius used the occasion to copiously take notes on

his pocket score. In addition, Bülow performed several sonatas at

the piano, the last five. Sibelius very

much appreciated, and carefully studied Bülow’s editorial

commentaries on these works. He also attended the concerts of the

Joachim Quartet, and the opus N°59 in F major inspired him to make

this curious commentary: ‘When to start the adagio, I imagine myself

on a swing in the moonlight. To the left a wall, on the other side a

marvellous garden with birds of paradise, shells and palms, etc.

Everything was dead and still, the shadows grew long and the odour

of an old library floated by. Nothing else but sighs could be

heard. It was Beethoven who sighed, zand when the theme in F major

appeared for the second time, he sighed even deeper. After a moment,

everything changed into large lakes of red water over which God

played the violin. Little by little I realised that is was Joachim

and his bow, De Ahma [the second violin] and the others appeared,

and finally myself J Sibelius.’

As a

result of the popular concerts of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra

could at last deepen his relations with Kajanus. The 11 February

1890, Kajanus conducted his symphonic poem Aino. Otto

Lessmann estimated the he he had transposed a very poetic and easily

understood subject into music in a very masterful fashion: the

suicide by drowning of the young and beautiful Aino trying to escape

the desires of the old Väinämoinen. Sibelius

later declared that he had been only been moderately impressed by

this piece of fifteen minutes long, strongly influenced by Wagner

and without doubt he had first learned of in Helsinki: Kajanus had

performed it the 7 March 1885, then again the 16 April 1886 and the

25 April 1889. It remains that this experience in Berlin was

partially at the origin of his own Kullervo, commenced in Vienna the

following year: Aino was inspired by the Kalevala and put the

words in Finnish into music: it is true they were anonymous words,

not from the Kalevala, but to the glory of the kantele. Sibelius

explained to Ekman: ‘The knowledge of this work was of an extreme

important to me. It opened my eyes to the marvellous possibility

offered to musical expression by the Kalevala, whilst the previous

attempts to interpret the national epic into music did not turn out

to be very stimulating. After having heard Kajanus’ Aino,

the idea of creating myself a work on a subject drawn from our own

national epic occupied more and more my imagination.’

As a

result of the popular concerts of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra

could at last deepen his relations with Kajanus. The 11 February

1890, Kajanus conducted his symphonic poem Aino. Otto

Lessmann estimated the he he had transposed a very poetic and easily

understood subject into music in a very masterful fashion: the

suicide by drowning of the young and beautiful Aino trying to escape

the desires of the old Väinämoinen. Sibelius

later declared that he had been only been moderately impressed by

this piece of fifteen minutes long, strongly influenced by Wagner

and without doubt he had first learned of in Helsinki: Kajanus had

performed it the 7 March 1885, then again the 16 April 1886 and the

25 April 1889. It remains that this experience in Berlin was

partially at the origin of his own Kullervo, commenced in Vienna the

following year: Aino was inspired by the Kalevala and put the

words in Finnish into music: it is true they were anonymous words,

not from the Kalevala, but to the glory of the kantele. Sibelius

explained to Ekman: ‘The knowledge of this work was of an extreme

important to me. It opened my eyes to the marvellous possibility

offered to musical expression by the Kalevala, whilst the previous

attempts to interpret the national epic into music did not turn out

to be very stimulating. After having heard Kajanus’ Aino,

the idea of creating myself a work on a subject drawn from our own

national epic occupied more and more my imagination.’

In

October 1889, Wegelius had had performed during the one hundredth

concert of the Institute two movements of the quartet in A minor.

The 1 December, during a brief journey overseas, he made a detour to

Berlin to meet Sibelius. He estimated with optimism that his protégé

‘had mastered vocal polyphony with success and continued with

enthusiasm and energy his musical and artistic training’, which led

him, in March 1890, to ask him to send a choral piece for one of the

concerts of the Institute. Sibelius however showed a taste

for luxury that scandalised his friends. In a letter to Wegelius

dated 29 September 1889, he went as far as asking the Governor

General of Finland to obtain for him, as the beneficiary of a state

grant, free tickets for the Berlin Opera! Undignified, Wegelius

replied the 4 October: ‘There is no reason that you do not content

yourself with the seats that other musicians of your age are only

too happy to occupy. For 1.50 [Marks], you would surely have a seat

where you can see and hear.’ From Werner Söderhjelm, who observed him

closely, Jean received the same day and for the same reasons, a

severe reprimand.

In

Helsinki, Christian was worried. Contrary to his eldest brother who

he admired enormously and to whom he was entirely devoted, he had

his feet well on the ground. After having been received by the

Lerches, the 7 September 1889, he wrote very lucidly: ‘When you are

your brother, you are treated royally.’ At the same time he offered

many pieces of advice to his brother on the best way to manage a

budget, notably remarking that many Finnish students living in

Berlin spent less than in Helsinki. He did not miss the opportunity

to remind him – after the sale, to provide Jean’s needs, of certain

of his own clothes – that in order to obtain a new grant for the

following year, he absolutely had to present his candidature and

fill in the necessary forms. Between November 1888 and March 1889,

to cover the expenses of Sibelius, his family borrowed about 2,000

Finnish Marks, or the equivalent of the grant provided by the Senate

for his sojourn in Berlin. In April, mostly due to the praiseworthy

certificate attributed by Becker, Jean was given a university grant

of 1,200 Marks to complete the year, but his financial problems were

not however settled. This led Christian to comment the 2 May: ‘If

you think about it, you will see that during these last two months,

you have not raised the least question of money, so we know nothing

about what you are doing or hearing and how you are taking advantage

of life.’

One way

of taking advantage of life was to mix with the many foreign groups

of musicians and artists in Berlin. Other than two Americans, the

cellist Paul Morgan and the violinist and conductor Theodore

Spiering (1871-1925), later violin soloist of the New York

Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Mahler, the circle into which

Sibelius was introduced to was mostly composed of Scandinavians.

These included two Danes, the violinist and composer Fini Henriques

(1867-1940), student of Joachim and ‘bohemian amongst bohemians’,

and the violinist Fredrik Schnedler-Petersen (1867-1938), who was

also a student of Joachim and later became orchestra leader in Turku

then the Copenhagen Tivoli Concert Hall. There were also three

Norwegians: the writer Gabriel Finn, the pianist, Alf Klingenberg

(1967-1944), who admitted spending more time flirting than on

musical scales, and above all the composer Christian Sinding

(1856-1941), the eldest amongst them. Sinding was in fact living in

Leipzig, but often came to Berlin with his violinist Ottakar Novacek

(1866-1900), student of the great Adolf Brodsky (1851-1929). When he

joined the group, Adolf Paul – who had completed his metamorphosis

from pianist to writer – arrived penniless from Weimar. On Sundays

they went in a procession goose stepping to the along the

Berlinerstrasse to a place called Augustinerbräu, where the others

forewarned by the noise started to shout: Die Schweden kommen!

(The Swedes are coming) They were accompanied by young women who, to

believe Adolf Paul, studied the musicians with more assiduity than

the music.